British Prime Minister Liz Truss enjoyed only seven days of full power before global economic forces effectively destroyed her government. PHOTO: REUTERS

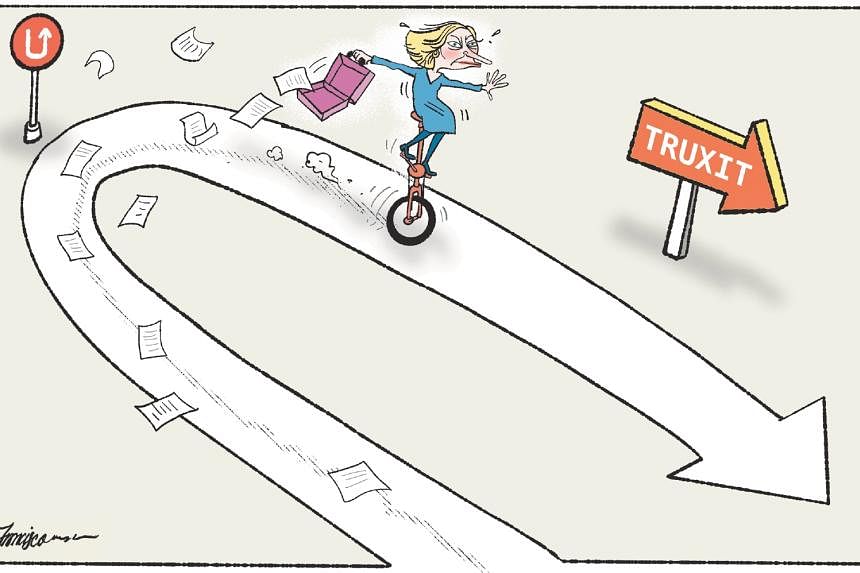

Whatever you may think of them, the British used to enjoy the reputation of a solid, well-run and responsible nation. A centuries-old history of peaceful political change, with none of the coups, revolutions or civil wars that seem to have afflicted most other countries worldwide. A robust parliamentary system of government in which just two political parties take their turns in holding power based on electoral procedures that produce clear-cut results and solid governments with none of the unpredictable and often unstable coalition-making that afflicts most of the rest of Europe. To be sure, the country’s politicians have always been of variable quality. But the United Kingdom’s civil service was highly rated for its professionalism and integrity, and so was its legal system, still considered an advantage and often touted as a national asset by many countries around the world. That’s why Britain’s sudden descent into crisis looks so surprising. In just a few weeks, the credibility of some of the most critical institutions in British national life, including the prime minister, the Treasury, the Bank of England, the ruling Conservative Party, and the nation’s asset management industry, were all torn to shreds. The country’s currency has sunk to its lowest levels in half a century, and the risk premium international investors demand to lend money to Britain is among the highest in the industrialised world. For the first time in modern history, the British government was forced to bow to the pressure of global financial markets and withdraw a budget it had introduced only two weeks beforehand. And in another highly unusual move, the International Monetary Fund issued a rebuke to Britain using language otherwise reserved for those who manage the economies of poor and vulnerable developing nations. Truss versus lettuce Consequently, British Prime Minister Liz Truss, who assumed office only last month, had to ditch her policies before these were even tried, and the speculation in London is that her days are numbered. The influential Economist newspaper had pointed out that, if one ignores the extended period of official mourning for Queen Elizabeth II – a period during which all politics were suspended – Ms Truss enjoyed only seven days of full power before the forces of the global economy effectively destroyed her government. That, The Economist suggested, is more or less the supermarket “shelf-life of the lettuce”. Liz Truss may never recover from this cruel jibe: a British tabloid newspaper is currently offering its readers a live video stream of a lettuce head and a photograph of the Prime Minister, accompanied by the question, “which wet lettuce will last longer?” Britain as a whole is now the butt of international jokes. Politicians in Italy – a country that will soon get its 70th government in almost as many years – have suggested that one of their retired prime ministers may be sent to London to try his hand at managing the British because he can’t do any worse than Britain’s politicians. Mr Kyriakos Mitsotakis, the Prime Minister of Greece, a country that a decade ago had to be bailed out from national bankruptcy by global financial institutions, told Ms Truss’ government tongue-in-cheek that if they “need experience in dealing with the International Monetary Fund, we’re here to help”. While the attention is on the UK experience, other economies and major currencies are also currently experiencing global pressure. The British pound may be down around 18 per cent to 20 per cent, but the euro is about 15 per cent weaker, and the Chinese renminbi dropped by an average of 11 per cent against the US dollar. The Bank of Japan recently spent an estimated US$21 billion (S$30 billion) trying to prop up the yen, to no avail. However, credibility is everything in politics, finance and economics, and the UK government finally managed to lose all of these. Britain’s previously admired institutional framework and its hard-won reputation of certainty in financial policy went down the pan over the past two weeks. And financial volatility is accompanied by political volatility. Between 1990 and 2010 – two decades – Britain was ruled by only three prime ministers. But from 2010 to now - just over one decade - the country has already known four additional prime ministers and may yet be ready for a fifth. Furthermore, no less than four politicians have served as finance ministers since January this year. These are chaotic politics Italian-style, minus the sun-drenched beaches or the delicious pasta.

The problem of Ms Truss was not necessarily just the financial figures she peddled but the fact that her ill-conceived budget became totemic for a more comprehensive loss of British political and economic credibility, which has been cumulative over several years.

But it won’t be easy to get out of this rut. King Charles III best summed up the national mood when he recently welcomed Prime Minister Truss to an audience with “dear, oh dear!

https://omny.fm/shows/in-your-opinion/is-the-nominated-member-of-parliament-scheme-losin

Related posts:

Liz Truss takes over a Britain in decline and in severe crisis: Martin Jacques

UK PM candidate's reported 'China threat' label plan 'an irresponsible vote-puller', no good for solving its own problems: analysts...

Students at Zhejiang Guangsha Vocational

and Technical University of Construction celebrate the upcoming 20th

National Congress of the C...

Strong leadership core to provide ‘certainty,

cohesion and strength’ in new journey A huge artificial flower

basket decorates Tian'anm...

No comments:

Post a Comment