Tweet

Internet Mourns Steve Jobs' Death

The news of Steve Job’s death caught the social media world by storm late Wednesday, with an outpour of people thanking the tech visionary for changing the way they live their lives.

Apple announced in a statement posted to its company site that its founder and former CEO died after his long battle with pancreatic cancer. In 2004, Jobs received a liver transplant and took several medical leaves of absences in recent years before finally resigning as CEO of Apple this summer.

“You inspired millions and changed the way we look at technology,” Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg wrote on his Facebook page. “No yardstick of quality could measure your actions.”

At press time, nearly 65,000 people “liked” Zuckerberg’s status, with many adding their own condolences to the message.

Facebook members also flocked to Job’s profile page to share their condolences. Many also took to the wall of Steve Wozniak, Job’s long-time business partner and Apple co-founder. [Read: Steve Jobs and Apple Through The Years (Infographic)]

“My condolences, Steve, on the passing of your business partner and friend,” wrote Bruce Ansley from Baltimore, Maryland. “Together you helped usher in a new era and countless lives have been enhanced because of your efforts and that of Steve Jobs, may he rest in peace.”

Microsoft Chairman Bill Gates wrote a message on Facebook to address the news:

“Steve and I first met nearly 30 years ago, and have been colleagues, competitors and friends over the course of more than half our lives. The world rarely sees someone who has had the profound impact Steve has had, the effects of which will be felt for many generations to come,” Gates wrote."I will miss Steve immensely."

President Barack Obama also released a statement on WhiteHouse.gov: “Michelle and I are saddened to learn of the passing of Steve Jobs. Steve was among the greatest of American innovators - brave enough to think differently, bold enough to believe he could change the world, and talented enough to do it,” Obama said.

“By building one of the planet’s most successful companies from his garage, he exemplified the spirit of American ingenuity,” Obama said. “By making computers personal and putting the internet in our pockets, he made the information revolution not only accessible, but intuitive and fun.”

Meanwhile, phrases such as “ThankYouSteve,” “RIP Steve Jobs” and “iSad” immediately began to trend on Twitter following the news. “Pixar” also shot up to the top of the trending list, as many remembered Jobs’s role as former Pixar chief and Disney executive.

Those in the tech industry weren’t the only ones to share words of sympathy on social networking sites: “Steve lived the California Dream every day of his life and he changed the world and inspired all of us,” Arnold Swarzenegger wrote on Twitter.

News of Jobs’ death comes one day after the company unveiled the fifth generation of the iPhone, the iPhone 4S, which Jobs played in integral role in developing.

“I have always said that if there ever came a day when I could no longer meet my duties and expectations as Apple’s CEO, I would be the first to let you know,” Jobs wrote in a letter released by the company when he left. “Unfortunately, that day has come.”

This story was provided by TechNewsDaily , sister site to LiveScience. Reach TechNewsDaily senior writer Samantha Murphy at smurphy@techmedianetwork.com.Follow her on Twitter @SamMurphy_TMN

Newscribe : get free news in real time

Newscribe : get free news in real time

When sober, F. Scott Fitzgerald may have been devastatingly intelligent, but he got it dead wrong when he wrote "there are no second acts in American lives."

Think Elvis, for example. Or lefty sinkerballer Tommy John of the eponymous surgery. Or, for that matter, Grover Cleveland, whose two acts as US president were separated by a four-year intermission.

In the business world, however, second acts are rare. In the corporate rat race, if you slip in Act I, you're trampled by your fellow rodents – there's no "Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow" on that unforgiving stage.

Except for Steve Jobs.

The career of Apple's cofounder and savior not only had a second act, but a long and successful third act that ranged from his return to Apple in 1997 to his resignation this August.

And to further give the lie to Mr. Fitzgerald, Jobs' second act held true to the dramaturgical dictum that as the curtain closes on Act II, our protagonist should be at the end of his rope, facing seemingly insurmountable odds.

Think The Empire Strikes Back, Act II of the original Star Wars trilogy. Think the Red Sox being down three games to zip against the Yankees in 2004. Think Steve Jobs at the end of 1993, with NeXT's hardware business sold at fire-sale prices and Disney stopping the development of Pixar's salvation, Toy Story.

The end of Jobs' redemptive and triumphant Act III, his death on Wednesday, could be thought to have turned his drama into a tragedy – but possibly more from our points of view than from his. By all accounts, he retained throughout his life the sense of light mortality that he gained when studying eastern philosophies in his youth.

"We're born, we live for a brief instant, and we die." he told Wired in 1996. "It's been happening for a long time."

Speaking at Stanford University in 2005, he said, "No one wants to die. Even people who want to go to heaven don't want to die to get there. And yet death is the destination we all share. No one has ever escaped it. And that is as it should be, because Death is very likely the single best invention of Life. It is Life's change agent."

And in 2008 he told Fortune, "We don't get a chance to do that many things, and every one should be really excellent. Because this is our life.

"Life is brief, and then you die, you know? So this is what we've chosen to do with our life."

And so here's a recounting of the life that Steve Jobs chose – and the life that chose him.

Jobs' biological parents were Joanne Schieble of Green Bay, Wisconson, and Syrian-born Abdulfattah Jandali, unmarried, both 23, and both students at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. It being the straight-laced mid-1950s, for the birth they secretly travelled to San Francisco, a few miles north of a sleepy, orchard-filled patch of Northern California that Jobs would one day help transform into Silicon Valley.

Adoptive father Paul, described by son Steve as "a sort of genius with his hands" in a 1985 Playboy interview, "used to get me things I could take apart and put back together."

Just as, in his later years, he took apart and put back together the company he founded, Apple Computer, when he returned to it in 1997 after a palace coup in 1985 had forced him out of the company that he had founded on April Fools' Day 1976 with Steve Wozniak and Ronald Wayne.

But we're getting ahead of ourselves.

The Jobs family moved to 2066 Crist Drive in Los Altos in the heart of pre-silicon Silicon Valley when Steve was five years old. As a kid, Jobs admitted, he was "a little terror." Today he might have been diagnosed as showing symptoms of ADHD – attention deficit hyperactivity disorder – and have been Adderalled or Ritalinned into submission.

"You should have seen us in third grade," Jobs described himself and his pint-sized co-revolutionaries. "We basically destroyed our teacher. We would let snakes loose in the classroom and explode bombs."

The 1950s may not have been enlightened enough to have accepted Schieble and Jandali's out-of-wedlock child, but neither was it a time when exploding bombs in a public school would call down the wrath of the Department of Homeland Security. In those days, Jobs' behavior was merely part of the "boys will be boys" ethos.

A fourth-grade teacher, Imogene Hill, who Jobs described as "one of the saints in my life," helped tame his rambunctiousness – partially by bribing him with cash if he'd finish his work, according to Anthony Imbimbo's biography written for young adults, Steve Jobs: The Brilliant Mind Behind Apple.

At age 12, Jobs met his first computer. HP engineer and neighbor Larry Lang took Jobs under his wing and, according to Jobs, "... spent a lot of time with me, teaching me stuff." Lang took Jobs and other kids to HP for lectures. "They showed us one of their new desktop computers and let us play on it. I wanted one badly."

At age 12, Jobs met his first computer. HP engineer and neighbor Larry Lang took Jobs under his wing and, according to Jobs, "... spent a lot of time with me, teaching me stuff." Lang took Jobs and other kids to HP for lectures. "They showed us one of their new desktop computers and let us play on it. I wanted one badly."

When in junior high, Jobs hung out with his friend and fellow geek Bill Fernandez, who – fortunately for the future of personal computing – lived across the street from the Wozniak family, whose son Steven was an inveterate electronics tinkerer.

Steve Wozniak was born in August 1950, making him five years older than Jobs. Despite their age difference, they bonded over their shared love of both electronics and pranks.

In 2007, when giving a Macworld Expo presentation, Jobs' slide-changing clicker malfunctioned. To fill time, he told his audience about one prank that he and Wozniak played when the older prankster was a student at the University of California at Berkeley:

When he was in his mid-teens, Jobs and Wozniak met the famous – infamous? – phone phreaker John Draper (aka Cap'n Crunch, so named after he discovered that a whistle given away in the eponymous cereal could phool fool AT&T's phone system). Inspired by the good Cap'n's success, Wozniak built what was then called a "blue box" – an electronic device that enabled him and friend Jobs to make free phone calls worldwide.

"The famous story about the boxes is when Woz called the Vatican and told them he was Henry Kissinger," Jobs told Playboy. "They had someone going to wake the Pope up in the middle of the night before they figured out it wasn't really Kissinger."

The blue box was Wozniak and Jobs' first commercial product, and established the relationship that would eventually result in the creation of Apple Computer: Wozniak would design, and Jobs would sell.

After high school – and after he had abandoned the blue-box business – Jobs headed off to Reed College in Portland, Oregon, then a notorious hippie haven, well-suited to increasingly hippified Jobs.

He lasted one semester, but continued to live on-campus – not a problem at Reed, nor for that matter at any number of schools during the laid-back early 1970s.

Don't laugh – you went to high school, tooAfter returning to his family home in 1974, Jobs talked himself into a job at Atari, the pioneering videogame firm that was rolling in cash due to the wild success of its pioneering arcade game, Pong.

Don't laugh – you went to high school, tooAfter returning to his family home in 1974, Jobs talked himself into a job at Atari, the pioneering videogame firm that was rolling in cash due to the wild success of its pioneering arcade game, Pong.

His position at Atari got him a tech-troubleshooting trip to Germany, which he extended into a classic hippie pilgrimage to India, where he wandered as an alms-begging mendicant, and famously had his head shaved by a highly amused Indian holy man.

After returning to California – shaved head and all – Jobs was rehired by Atari, and hooked back up with Wozniak. At that point, Wozniak was working at HP, but he would visit Jobs at night at Atari to play that company's Gran Track game for free.

"Woz was a Gran Track addict," Jobs told Playboy. "He would put great quantities of quarters into these games to play them, so I would just let him in at night and let him onto the production floor and he would play Gran Track all night long." But Jobs wasn't being merely magnanimous: "When I came up against a stumbling block on a project, I would get Woz to take a break from his road rally for ten minutes and come and help me."

Jobs also used Wozniak's smarts to design that company's Breakout game. According to Jeffrey Young and William Simon is their unauthorized biography, iCon Steve Jobs, along with other sources, Jobs took credit for the design and snookered Wozniak out of his rightful share of the pay and bonus that Jobs was given for "his" work.

The "Good Steve" versus "Bad Steve" dynamic that would mark Jobs' persona for the rest of his life was already in place.

Shortly after that epoch-making event, a group of electronics enthusiasts formed the Homebrew Computer Club. In addition to Jobs and Wozniak, members included such soon-to-be-luminaries as George Morrow, Adam Osborne, and Lee Felsenstein. It was among that heady company that Wozniak developed the first prototypes of what was to become the Apple I.

Where Wozniak saw a diverting intellectual challenge, Jobs saw a business opportunity. After the debut of the Altair, "microcomputer" kits were appearing right and left, and Jobs believed that Wozniak's designs – one for a color-capable computer, no less – could find a market.

After some cajoling, Wozniak agreed to Jobs' suggestion that they form a company, and that the company should be named Apple Computer. Although the true source of the name remains cloudy – was it that apples were grown on a commune that Jobs had recently visited, the fact that "Apple" would appear ahead of "Atari" in the phone book (remember phone books?), a tribute to The Beatles? – it was Jobs' idea and Wozniak agreed to it.

On April 1, 1976, Jobs, Wozniak, and Ronald Wayne – a friend of Jobs from Atari who dropped out of the new company less than two weeks later (and who recently published an autobiography) – signed the paperwork that created Apple Computer. With an order for 50 fully assembled Apple I computers from a tiny Mountain View, California, geek emporium called the Byte Shop, and with the proceeds of the sale of Wozniak's HP-65 calculator and Jobs' VW van, the company was up and running.

The Apple I was less than a rip-roaring success, selling around 200 units, total. Jobs reportedly wanted to sell it for $777.77, but Wozniak thought that was too expensive, so the price was dropped to $666.66 – around $2,500 in today's dollars.

Wozniak's next creation, the Apple II, was a different animal entirely. Wozniak said it should have expansion slots, so it had expansion slots. Jobs said i shoul run without a fan, so they hired someone to invent the smaller, cooler, switching power supply.

By far more important, however, was a decision by Jobs and Wozniak that would affect all of Apple's future product development: the Apple II would be a complete system designed for ease of use, simple operation, and consumer friendliness. Industrial design was also on Jobs' mind: no screws disturbed the Apple II's plastic exterior – they all were on the bottom of its all-plastic case.

Jobs made one more key move at this time: he landed a key investor and business adviser, Mike Markkula, who got the two founders to incorporate Apple in January 1977. Markkula also introduced the duo to Mike Scott, and convinced them to hire him as president of the fledgling outfit. Scott and Jobs clashed almost immediately, the first of many such battles that would lead to Jobs' eventual ouster.

On April 17, 1977, the Apple II debuted at the West Coast Computer Faire, and – as each and every Apple press releases noted for many years afterwards – "ignited the personal computer revolution."

"They showed me really three things," he said in an interview in the PBS series "Triumph of the Nerds" in 1996. "But I was so blinded by the first one I didn't even really see the other two" – those two being the object-oriented programming language SmallTalk, created by Alan Kay and others, and a fully network collection of over 100 Xerox Alto computers hooked up over Bob Metcalfe's Ethernet.

"I was so blinded by the first thing they showed me which was the graphical user interface," Jobs recalled. "I thought it was the best thing I'd ever seen in my life." He left Xerox PARC determined that Apple would bring GUI-based computing to the masses.

Apple's first effort – largely created without Jobs, who was soon frozen out of the project – was the $10,000 dinosaur-with-a-lousy-floppy-drive-named-"Twiggy" known as the Lisa, which Jobs inexplicably named after the daughter he had conceived in 1977 with then-girlfriend Chris-Ann Brennan but had never formally acknowledged (although Apple insisted that Lisa was actually an acronym for Local Integrated Software Architecture).

After being booted from the Lisa project, Jobs' next chance came thanks to Jef Raskin, an Apple employee who was interested in building an inexpensive computer suitable for the mass market. Raskin had developed a prototype in late 1979 that he dubbed the Macintosh. It wasn't a GUI-equipped device – that came later.

Jobs essentially hijacked Raskin's Macintosh project in 1981, after it had been joined by such now-famous Apple names as Burrell Smith and Bud Tribble. Jobs shortly snagged programmers Andy Hertzfeld, Bill Atkinson, and others. Job's autocratic managment style was soon identified by the team as his "reality distortion field".

The development of the Macintosh continued with the team ensconced in a building over which flew a pirate flag, inspired by a quote attributed to Jobs in multiple wordings, but which essentially could be summarized as "Why join the navy if you can be a pirate?"

The Lisa beat the Macintosh to market by a year. When attending the New York rollout, Jobs held a meeting with then-Pepsi president John Sculley, with the goal of enticing him to take the reins at Apple, Mike Scott having been forced out by Markkula the previous year.

At that meeting, Jobs challenged Sculley with the now-famous quote: "Do you want to spend the rest of your life selling sugared water or do you want a chance to change the world?", as recounted by the Pepsi prez in his 1987 book, Odyssey. Sculley accepted Apple's offer.

It was a masterful sales job by Jobs – but one that he'd live to regret.

But before that miscalculation would come back to haunt him, Jobs had one major triumph to enjoy. On January 22, 1984, during the third quarter of Super Bowl XVIII, while the LA Raiders were busy trouncing the hapless Washington Redskins, Ridley Scott's celebrated 1984 ad told viewers: "On January 24th, Apple Computer will introduce Macintosh. And you'll see why 1984 won't be like '1984'."

Although that showing is popularly known as the one and only time that the ad was televised, it wasn't. Jobs & Co had pulled off another bit of manipulative chicanery. 1984 had been televised once before: on December 15, 1983 at 1am in Twin Falls, Idaho, a town of about 55,000 souls at the time – a ruse that enabled 1984 to be considered for 1983 advertising awards.

Soon after its showy introduction, it bacame apparent that the Macintosh was not going to be the instant hit that Jobs had predicted. Plagued by a 128KB memory allotment – low even for that time – plus a lack of expanability, no hard drive, and other limitations, it failed to attract a critical mass of software developers.

It didn't help, either, that the Mac's graphical user interface was unfamiliar to the developer community – although there was one young, up-and-coming developer who thought the Mac was worth investing in: Bill Gates.

Mac sales tanked. Jobs reportedly blamed everyone but himself – including Sculley – for the seeming failure of his pet project.

He also made the strategic error of alienating both his once-friend Steve Wozniak and the company's Apple II team – still responsible for the bulk of the company's revenue – by ignoring the company's one successful product during an annual meeting.

Wozniak quit Apple - loudly. According to iCon, Wozniak tore into Jobs and his supporters during his resignation, saying: "We had a shareholders' meeting last week and the words 'Apple II' were not mentioned once." Jobs was running out of friends at Apple.

Jobs then made another strategic error by attempting to work behind Sculley's back to get him fired. The machinations involved in his struggle with Sculley and his supporters were complex and many-layered – and the stuff of legend – but in the end Sculley won.

At the end of May 1985, Sculley convinced Apple's board of directors to remove Jobs as general manager of the Macintosh division and deny him any day-to-day operating role in the company – although he was allowed to retain his position as board chairman. Jobs described Sculley's withdrawl of support as being like when "somebody punch[es] you in the stomach and it knocks the wind out of you and you can't breathe."

On June 1, in an article entitled "Apple Co-Founder Jobs Demoted", the San Jose Mercury News reported that Apple said Jobs would take on "a more global role in product innovations and strategies."

After being "demoted," Jobs spent some time in Europe, and when he returned to Cupertino he was asked to move out of his office to a separate building he nicknamed "Siberia", where he pondered his next move. Pun intended.

"I went for a lot of long walks in the woods and didn't really talk to a lot of people," Jobs said about the period ofter his exile to Siberia. But then he began to quietly put together a team of Apple senior engineers to launch the company that eventually became known as NeXT.

On August 15, 1985, Apple's stock was at its lowest point in its history, before or since, closing – when adjusted for three splits since – at $1.8125. In September 1985, after another bout of internecine warfare with Apple management, Jobs tendered his resignation.

In early 1986, Jobs finished selling off all but one of his shares of Apple stock. He kept that single share, he is said to have commented, in order to keep receiving the company's annual reports.

The same Merc article that reported his ouster also said: "As of January, Jobs still owned 11.3 percent of Apple stock, a block that was worth about $120 million Friday, when Apple closed at 17 3/8, down 1/4." As of January 2011, when Apple's market capitalization was hovering around $315bn, 11.3 per cent of Apple stock was worth approximately $35.6bn.

In an interview with Bloomberg Businessweek on October 20, 2010, John Sculley said: "Looking back, it was a big mistake that I was ever hired as [Apple's] CEO."

Jobs' desire to "build things" led to him gathering the five senior Apple engineers he had been courting and hiring them as the core of his next computing effort, which eventually became known as NeXT.

Apple management, to put it mildly, wasn't pleased, and started legal action against Jobs for a "nefarious scheme" in which, they alleged, he was not only poaching senior staff, but also planning to use proprietary Apple technology and confidential information.

That lawsuit was eventually dropped, but not before Jobs fired back in the press, saying in the same Newsweek interview: "There is nothing ... that says Apple can't compete with us if they think what we're doing is such a great idea. It is hard to think that a $2 billion company with 4,300-plus people couldn't compete with six people in blue jeans."

Jobs soon had a great stroke of luck: billionaire entrepreneur and eventual presidential candidate H. Ross "giant sucking sound" Perot became NeXT's principle investor, as well as – as BusinessWeek put it in an October 1988 cover story – its "head cheerleader".

The workstation line that NeXT created was aimed at scientific and academic users who needed brawny computing power on their desks. It was inarguably elegant, but sold poorly. However, one of those workstations' supported operating systems, Next System (which morphed into NeXTStep), was eventualy key to Jobs returning to Apple in late 1996.

A quick side note. There were at least five different ways of writing NeXTStep, with four being official usages that depended upon exactly what parts or version of it you were referring to: NeXTStep, NeXTStep, NeXTSTEP, and NEXTSTEP – the fifth, which NeXT acknowledged but didn't use, was NextStep. For the sake of sanity, we're going to consistently use NeXTStep. The same goes for the related API definition, OpenStep/OPENSTEP, aka NEXTSTEP 4.0.

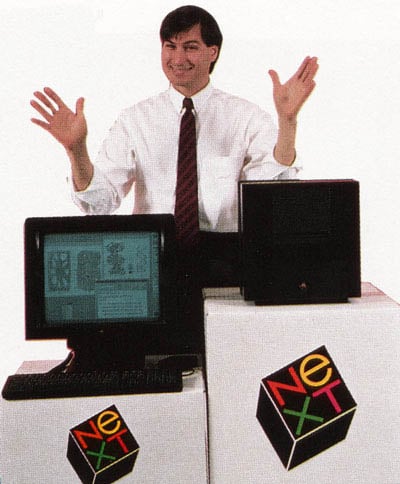

The original NeXT Computer seemed to be Jobs' attempt to one-up Apple's Macintosh. It was powered by a Motorola 68030 processor, 68882 FPU, and DSP56001 digital signal processor, all running at 25MHz. When the NeXT Computer debuted in prototype form on October 12, 1988, the top-end Mac of the time – the IIfx – had a 16MHz 68030 and 68882, and no DSP.

Other better-than-Mac features of the NeXT Computer included Display PostScript and built-in Ethernet. The full NeXT system included a 17-inch monochrome 1120-by-832 Megapixel Display – Apple's 1152-by-870 Two-Page Monochrome Display wasn't released until March of 1989. NeXT also offered a 400-dpi laser printer that, since the computer itself included Display PostScript, cost just $2,000 – a steal compared with Apple's 300-dpi LaserWriter IINTX, which had a built-in PostScript interpreter that helped boost its list price to $6,999.

Jobs also added a typical 'I know what's best" touch: rather than a hard drive and/or floppy drive, the NeXT Computer included a 256MB magneto-optical drive – an relatively unusual item in those days – which the original NeXT brochure described as being "bound to become the standard technology of the '90s."

There was, however, a bay inside the NeXT Computer for a hard drive, should you choose to install one. As the brochure pointed out: "Its possible configure [sic] your NeXT system to allow access to truly enormous amounts of storage - approaching one gigabyte and more."

The NeXT Computer was a cubical black box, which led to it often being called the NeXT Cube. That name was then officially applied to the company's next product, 1990's 40MHz 68040–equipped NeXTcube, which appeared along with the color-capable NeXTdimension. The final NeXT line, the NeXTstation, flattend out the cube into a more-standard "pizza-box" shape and added a floppy drive.

But none of NeXT's nifty hardware offerings sold well – although some boxes are still in use. No official total-sales number is available, but it's generally accepted to be in the range of 50,000 – from the debut of the original NeXT Computer in 1988 to the demise of the black beauties in 1993.

There's one possibly apocryphal anecdote about Jobs' difficulty – and naiveté – in selling NeXT boxes that bears retelling. According to Alan Deutschman's The Second Coming of Steve Jobs, Jobs presented both black and white and color versions of his workstation to a group of Disney execs, hoping to convince them to put in a large order.

In his audience was Jeffrey Katzenberg, head of Disney's feature-film division. After Jobs said that the color NeXT box would put image-making power in the hands of ordinary people, Katzenberg interrupted him. The bare-knuckles exec complimented the black-and-white unit, but he had a different opinion of the color version

"'This is art,' Jeffrey said," according to Deutschman. "'I own animation, and nobody's going to get it.' His voice was fierce and intimidating and commanding. 'It's as if someone comes to date my daughter. I have a shotgun. If someone tries to take this away, I'll blow his balls off.'"

Jobs' reality-distortion field was breached.

Although the NeXT hardware had its fans, sales were skimpy. However, NeXT's Unix-based operating system and its set of libraries, services, and APIs eventually known as OpenStep, attracted many programmers as devoted fans.

Tim Berners-Lee, for example, wrote the first browser, WorldWideWeb, on a NeXT. "This had the advantage that there were some great tools available," he wrote. "[I]t was a great computing environment in general. In fact, I could do in a couple of months what would take more like a year on other platforms, because on the NeXT, a lot of it was done for me already."

The NeXT System's application-development prowess would eventually change Steve Jobs' life – but not before NeXT's hardware business imploded.

George Lucas – of American Graffiti and Star Wars fame – had divorced in 1983 and split his wealth with his wife, as required by California law. He needed cash, in part to finish his next film, Howard the Duck.

Lucas' company, Lucasfilm, had a small division that had created computer-generated imagery before it was even called CGI – the "Genesis Effect" sequence in 1982's Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan is an early example of its groundbreaking work.

Lucas offered the division to Jobs for $30m; Jobs eventually whittled him down to a $10m deal – $5m to Lucas and $5m to be invested in the company, according to The Wall Street Journal. Jobs dubbed his new company Pixar, and incorporated it on February 3, 1986. Howard the Duck opened on August 1 of the same year, and was reviled as one of the worst films ever made.

Jobs got the better part of the deal.

At first, Pixar was essentially yet another computer company, albeit one that focused on a narrow niche: high-end computer graphics. The company's Pixar Image Computer was Steve Jobs' Next Computer bumped up by an order of magnitude – or more.

Designed for weather, engineering, science, and medical imaging purposes – check out the 1987 demo reel – the first Pixar Image Computer cost $135,000, needed a $35,000 Sun or SGI workstation to run it, and sold poorly. The price dropped to $30,000 when a second stripped-down version, the P-II, was released. A much more powerful follow-on called the PII-9, however, was also much more expensive – its 3GB RAID array alone cost $300,000.

By all reports, although Jobs kept his eye on Pixar's hardware division, he didn't micromanage Pixar's animation creatives. One Pixar exec, Ralph Guggenheim, told Deutschman that Jobs visited Pixar's offices "no more than five times between 1986 and 1992, no exaggeration."

Jobs did, however, throw trendous amounts of cash at Pixar – but to sell the Pixar Image Computer, not to develop the animation output. It didn't work. Like Jobs' NeXT boxes, the Pixar Image Computer never caught on. Fewer than 300 were ever sold, and the business was sold to Vicom in 1990 for $2m. Vicom was bankrupt in a year.

Although Jobs reportedly tried to shut down Pixar's tiny animation group in 1987 and 1988, it started to become a profit center, producing commercials for the California Lottery, Lifesavers, Volkswagen, and others. Eventually, it became the saving grace of the company – along with the fact that Disney Studios was one of the Image Computer's main customers.

After the head-turning success of Pixar's computer-animated short Luxo Jr. and the Academy Award–winning Tin Toy, Jobs tried to salvage Pixar by selling a mass-market commercial version of the 3D software that had been used to create them and the animation group's money-making ads, RenderMan.

That effort was unsuccessful, due in part to RenderMan's complexity. Soon Jobs had two companies – NeXT and Pixar – both on the ropes. Jobs continued to fund the ailing Pixar through a line of credit he had set up, but forced all employees to return their shares in the company, making him the sole owner.

However, in the fall of 1990, a few of Pixar's top creative began discussions with Disney Studios about using their software and expertise to create the first full-length, computer-generated feature film. In 1991 Jobs joined the negotiations, and by May 1991 Pixar had a a three-movie contract with Disney, to begin with Toy Story.

Although Jobs may not have known it at the time, that deal and the fact that he was the company's sole owner was soon to make him very, very rich – but not before his career his rock bottom.

An article in Fortune in February of that year makes clear the ambivalence that the industry felt for Jobs at the time. "Sometimes it's hard to tell whether Steve Jobs is a snake-oil salesman or a bona fide visionary," it reads, "a promoter who got lucky or the epitome of the intrepid entrepreneur."

The article goes on to describe Jobs' last-ditch efforts to save NeXT by porting its NeXTStep operating system to run on Intel 486 processors – NeXT boxes ran on Motorola 68030s and 68040s – then licensing it to other companies. The port, to be called NeXTStep 486, had been announced the previous January at NeXTworld Expo, but it hadn't yet appeared.

"It's always taken me twice to get it right," Jobs is quoted as saying. "You never heard of the Apple I."

At the time, Jobs considered Microsoft's Cairo project and Apple and IBM's Taligent effort to be NextStep's prime competitors – and he wasn't too worried about the latter. "Apple has a thousand software engineers," he told Fortune, "who have realized that Taligent is their enemy." IBM, he said, "can't evangelize its way out of a paper bag."

The previous year, Jobs had courted and won a hard-nosed Brit, Peter van Cuylenburg, to be NeXT's president and COO – and to please NeXT's 17.9 per cent investor, Canon. His tenure proved brief.

After crowding out long-term NeXTers – "I've put pressure on the company, and not everyone was willing or able to accept it," he told Fortune – van Cuylenburg announced that he was leaving NeXT in March 1993, either fired, resigning. Or a bit of both.

As van Cuylenburg told InfoWorld: "Steve [Jobs] wanted to regain control of the company. There wasn't a meaningful job for me to do."

There are unconfirmed reports that before van Cuylenburg left NeXT, he went behind Jobs' back and called Scott McNealy at Sun, asking him to buy NeXT and install him as CEO. True or not, Sun didn't bail out NeXT.

The same day that the Fortune article appeared in which Jobs discussed both hardware and software plans for NeXT, InfoWorld ran a front-page article that began: "Next Computer will transform itself into a software company, ceasing production of its workstation line and laying off a large number of employees, sources said."

On February 10, Jobs confirmed the rumor. Canon bought the hardware business for an undisclosed amount after having invested $120 in cash and $55m in debt. Of NeXT's 530 remaining employees, 230 were laid off, and another 100 went to Canon. The remaining 200 stayed with Next Software.

Jobs tried to put a positive spin on leaving the hardware business. "We understand we could work really hard for the next few years and emerge as a good second-tier hardware company," he told The New York Times. "But ... we have a chance to be a first-tier software company."

In the InfoWorld article that leaked Jobs' plan to dump hardware and focus only on NeXT software, one analyst was quoted as saying "This is probably the first really smart business decision Jobs has ever made." He proved to be correct, though in ways he could never have imagined.

NeXTStep Release 3.1, shipped on May 25 at NextWorld Expo in San Francisco, included support for both Motorola and Intel instruction sets, combined in what NeXT called a Multiple Architecture Binary. The Intel-centric install became known as Release 3.1 for Intel Processors, renamed from NeXTStep 486 due to added support for Pentiums.

As upbeat as Jobs attempted to appear in public, however, his heart was in hardware – and he had ploughed millions of dollars of his now-dwindling fortune into NeXT, trying to prove that his tenure as Apple's founder was not a fluke.

When Canon held a now-famous auction on September 15, selling off NeXT's office furniture, manufacturing robots, cafeteria equipment, and unsold NeXT computers at fire-sale prices, Jobs' hardware days seemed over for good.

The next month, Jobs received another blow: after Pixar's creatives held a disasterous screening of their progress on Toy Story for Disney brass on November 19, Disney headman Jeffrey Katzenberg stopped development of the film that Jobs presumably hoped would save Pixar.

"Guys, no matter how much you try to fix it," Disney animation chief Peter Schneider told them, citing the unpleasant personalities of the film's two lead characters as presented in the screening, "it just isn't working."

For Steve Jobs, Christmas 1993 could not have been jolly.

In February, however, he received good news. After Disney halted the Toy Story project in its tracks, Pixar's creative genius John Lasseter and his staff had taken Katzenberg's criticism to heart, and had rewritten the script. When they took it back to Disney, Katzenberg green-lighted it. Pixar was back in the movie-making business.

At first, Jobs was less than excited about the project, and tried to peddle Pixar to a few potential buyers, including Microsoft.

The turnaround of Jobs' opinion of Pixar came when he attended a lavish Disney event in New York's Central Park in January of 1995 to showcase clips from two of that year's blockbuster animations: Pocahontas, scheduled for summer, and Toy Story, scheduled for the lucrative Thanksgiving time slot.

Ralph Guggenheim, Toy Story's coproducer, told Alan Deutschman that "Steve went bonkers" at the attention that the Pixar film received at the event, which was attended not only by Disney's top execs, including CEO Michael Eisner, but also New York mayor and celeb Rudi Guliani, plus assorted other VIPs.

"This was the moment when Steve realized the Disney deal would materialize into something much bigger than he had ever imaginied," Guggenheim recalled, "and that Pixar was the way out of his morass with NeXT."

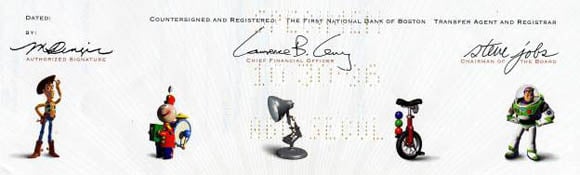

After that event, Jobs became more involved with the day-to-day workings of Pixar. In February, he hired away EFI's CFO Lawrence Levy to take the same position at Pixar, with the goal of taking the company public – and, audaciously, to schedule the IPO for immediately after the Thanksgiving debut of Toy Story.

If the movie were to be a success, the buzz surrounding it would fluff the IPO. If it flopped, so would the IPO.

Toy Story debuted on November 22; the IPO was held on November 29. Toy Story was the number one movie in the US on its opening weekend, and went on to be number one for its first three weekends, then number one again during the Christmas/New Years holiday break.

Pixar's first feature was the number one grossing film of 1995, and went on to eventually gross exactly $361,958,736 worldwide, according to Box Office Mojo.

And the IPO? Shares of Pixar – a company that had lost money each year beginning in 1992 – had been pegged to be offered at $12 to $14 in a preparatory SEC filing, but opened at $22 during the first day of trading on the NASDAQ exchange. Shares rose as high as $49.50 during that day before settling back to $39.

Specimen Pixar IPO certificate with Steve Jobs' signature (source: Scripophily.com)

Specimen Pixar IPO certificate with Steve Jobs' signature (source: Scripophily.com)

Jobs held 80.2 per cent of Pixar's shares. The IPO made him a very wealthy man. As David Price put it in The Pixar Touch, "Following the IPO, his shares of Pixar were valued at more than $1.1 billion – and the rounding error on that figure was almost as much as the entire value of his Apple holdings when he left Apple a decade earlier."

And he missed Apple. "It was like the first adult love of your life," he told a New York Times reporter in November 1996, "something that is always special to you, no matter how it turns out."

Fortunately for Jobs, Apple was in the crapper. The much-ridiculed Newton hadn't taken off, Apple was hemorrhaging money from a poorly thought-through OS-licensing scheme, and thanks to its success with Windows 95, Microsoft was eating its lunch.

The Mac's operating system was creaky and unreliable, and efforts to replace it were going nowhere. Apple's "Pink" OS skunkworks had been merged with IBM to form Taligent, which eventually produced the IBM-only CommonPoint, which soon vaporized. Apple next – no pun intended this time – new-OS effort, Copland, was going nowhere fast.

The Mac's operating system was creaky and unreliable, and efforts to replace it were going nowhere. Apple's "Pink" OS skunkworks had been merged with IBM to form Taligent, which eventually produced the IBM-only CommonPoint, which soon vaporized. Apple next – no pun intended this time – new-OS effort, Copland, was going nowhere fast.

Apple's new, no-nonsense CTO Ellen Hancock decided that Copland was a lost cause, killed it, and in 1996 started shopping around for a third-party operating system to replace the Mac's operating system, at that time System 7.5.

Apple first made an offer to Jean-Louis Gassée, the man John Sculley had picked to replace Jobs as head of Apple's hardware division, to buy his company, Be, and its still-unfinished BeOS, which was slated to power the company's BeBox hardware. Gassée deemed the offer too low, however, and was holding out for $200m – an amount that Apple chairman and CEO Gil Amelio termed "outrageous".

Apple's discussions with Gassée were hardly a well-kept secret, and so – having an operating system of his own to peddle – Jobs called Cupertino. Amelio was out of the country, so Jobs left a message for Hancock.

"I was startled to see Steve Jobs had called," she recalled to the NYT, "but I returned it immediately."

"I was startled to see Steve Jobs had called," she recalled to the NYT, "but I returned it immediately."

During the ensuing conversation, Jobs was reported to have not made a sales pitch for

NeXTStep/OpenStep but only to have discussed operating systems in general – and, likely, Gassée and Be in particular. But it can only be assumed that Hancock, being nobody's fool, knew what was what.

A few days later, a couple of NeXT managers called Apple on their own, and Apple engineers met with them. Soon Jobs himself was invited to Cupertino to talk with Amelio, Hancock, and Apple strategist Doug Solomon. "It was the first time I had set foot on the Apple campus since I left in 1985," Jobs told the NYT.

A week later, NeXT and Be met separately with top Apple execs at a Palo Alto hotel frequented by the Silicon Valley geekerati, and the word was out: Jobs and Apple were courting one another.

And it wasn't only Jobs' operating system that Apple was interested in. "We always talked about him being on the inside," Hancock said at the time. "We're hoping he can show us where to go from here in emerging markets and technologies."

On December 20, 1996, Amelio announced the acquisition of NeXT Software. "We chose Plan A instead of Plan Be," the sooner-be-ex-Apple-CEO is reported to have quipped.

Then, on January 7, 1997, Amelio gave what many observers ridiculed as the most discombobulated, rambling keynote speech imaginable at Macworld Expo in San Francisco – one that your reporter once described as having "a lack of focus matched only by Apple's product line, which was lumbered with ill-performing Performas and other humdrum machines."

As Amelio mercifully brought his talk to an end, he invited Jobs on stage to demo what Apple had just bought: NeXTStep and its cutting-edge OpenStep development environment. After enduring well over an hour of Amelio's stultifying speechifying, the crowd went wild when Jobs bounded onto the stage, strutting and beaming as he showed off his slick software. His adoring fans bruised their palms with applause, and a new era – both for Jobs and for Apple – began.

And Hancock? The person who did more to return Steve to his "first adult love" than anyone else at Apple? Word soon began to circulate among Apple managers that, behind her back, Jobs dismissed her as a "bozo".

Of the $427 million in cash and stock that Apple paid for NeXT, Jobs took $100 million for himself and kept all 1.5 million shares of Apple stock that were part of the deal. No NeXT staffer got as much as a share.

Good Steve. Bad Steve.

However, despite all the buzz of a "palace coup", the lack of faith in Amelio by many Apple staffers, and the desire by many throughout Silicon Valley for him to take over, a BusinessWeek article from that period quotes Jobs as saying: "People keep trying to suck me in. They want me to be some kind of Superman. But I have no desire to run Apple Computer. I deny it at every turn, but nobody believes me."

Technically, Jobs may not have been running Apple, but he was certainly influential. He convinced Amelio to starve Sculley's pet project, the Newton. He talked Amelio into revamping his executive staff, and in 11 weeks, half of the eight were Jobs' recommendations, including Jon Rubinstein running hardware and Avie Tevanian running software – both of whom had worked with Jobs at NeXT.

Jobs lobbied for the demotion of Apple COO Marco Landi, Amelio agreed, Landi quit. Jobs lobbied against CTO Ellen "bozo" Hancock, and Amelio took R&D away from her. Jobs lobbied for cutting advanced R&D, and Amelio made plans to cut that department's budget by 50 per cent. Jobs lobbied for getting rid of poorly performing products and product-development efforts, and Amelio pulled the plug on the Performa line of consumer Macs, and stopped development of OpenDoc and its web-tool collection, CyberDog.

Jobs lobbied for the demotion of Apple COO Marco Landi, Amelio agreed, Landi quit. Jobs lobbied against CTO Ellen "bozo" Hancock, and Amelio took R&D away from her. Jobs lobbied for cutting advanced R&D, and Amelio made plans to cut that department's budget by 50 per cent. Jobs lobbied for getting rid of poorly performing products and product-development efforts, and Amelio pulled the plug on the Performa line of consumer Macs, and stopped development of OpenDoc and its web-tool collection, CyberDog.

Then on July 9, Apple's board of directors showed Gil Amelio the door, a move that The New York Times called an "abrupt ouster" that "casts doubt on whether the company that pioneered the personal computer industry can be revived." Hancock resigned along with him.

When making their announcement, the Apple board said that Jobs would take a larger role. They had offered him the position of CEO, which he declined, saying that he already was a CEO – at Pixar – and that one CEO position was enough. He did, however, agree to join the Apple board.

Jim McCluney, Apple's operations chief, told BusinessWeek of Amelio's good-bye and Jobs' hello. McCluney said he was called to a meeting with Amelio and Apple's top execs. "Well, I'm sad to report that it's time for me to move on," Amelio said. "Take care." And with that, after being Apple CEO for merely 17 months, Amelio left the room.

Jobs entered, McCluney recalls, and asked the execs, "OK, tell me what's wrong with this place." After a few timid replies, Jobs countered that what was wrong was Apple's products. And he had a firm opinion of what was wrong with them: "The products suck! There's no sex in them anymore!"

Soon afterwards, Jobs revealed what most observers had surmised when 1.5 million shares of Apple stock hit the market in June: those were the shares that Jobs had been given in the NeXT deal – he had sold them immediately after the six months for which he had agreed to hold them.

"Yes, I pretty much had given up hope that the Apple board was going to do anything. I didn't think the stock was going up," Jobs told Time magazine. "If that upsets employees," he added, "I'm perfectly happy to go home to Pixar."

That sale, however, turned out to be not the wisest financial move. Apple's stock shot up in August after Jobs made his most important announcement by far during his short tenure at Apple: a partnership with Microsoft.

On August 6, Jobs took the stage at Macworld Expo in Boston, and told the crowd of Apple fans that Apple and Microsoft had settled their long-running "look-and-feel" patent dispute, that Redmond had purchased $150 million in non-voting Apple stock and agreed not to sell it for a minimum of three years, and most importantly, Gates & Co. had promised to continue support for Microsoft Office on the Mac for five years.

At the time, fanatical Apple fanbois considered Microsoft the Evil Empire and Bill Gates the Great Satan. And Jobs hadn't exactly done his best to quell that sentiment. For example, in the 1996 documentary Triumph of the Nerds, he had said: "The only problem with Microsoft is they just have no taste. I don't mean that in a small way. I mean that in a big way, in the sense that they don't think of original ideas and they don't bring much culture into their products."

Jobs was not alone in that belief, and so after he announced the Microsoft deal at his Macworld keynote there were more than a few boos when Bill Gates appeared on a giant screen behind Jobs in a satellite feed – but those boos were drowned out by the applause of the more-rational Mac lovers in attendance who understood that an endorsement by mighty Microsoft was exactly what Apple needed.

Jobs chided the boo-birds. "We have to let go of this notion that for Apple to win Microsoft has to lose," he said. "We have to embrace a notion that for Apple to win, Apple has to do a really good job. And if others are going to help us, that's great, because we need all the help we can get."

Jobs chided the boo-birds. "We have to let go of this notion that for Apple to win Microsoft has to lose," he said. "We have to embrace a notion that for Apple to win, Apple has to do a really good job. And if others are going to help us, that's great, because we need all the help we can get."

Jobs also noted that "if we screw up and we don't do a good job, it's not somebody else's fault. It's our fault."

And he told a reporter from Time magazine that screwing up was very much on his mind. "Apple has some tremendous assets," he said, "but I believe without some attention, the company could, could, could – I'm searching for the right word – could, could..." Pause. "Die."

Jobs wasn't alone in his worries. Michael Dell, when asked what he'd do if he were running Apple, famously told an ITxpo97 crowd in October of 1997: "What would I do? I'd shut it down and give the money back to the shareholders."

In the summer of 1997 he swiftly terminated Apple's misguided operating-system licensing program, which was pulling sales away from Cupertino without increasing the Mac operating system's market share.

First, he refused to extend the same licensing deals that clonemakers had for System 7 to the new System 8, which was released on July 26. Then on August 30 he eliminated cloners participation in the Mac OS Up-To-Date program, which provided low-cost operating system updates for purchasers of new Macs. And finally, on September 2 he announced that Apple had purchased the preeminent clone-making licensee, Power Computing, for $100 million in Apple stock.

To be sure, there were clonemakers other than Power Computing – DayStar, Motorola, Pioneer, APS, MacTell, Akia, and MaxxBoxx – but they all soon got out of the business. UMAX lastest the longest, staying at the low end of the market, but finally gave up on May 27, 1998.

Soon after the purchase of Power Computing – on September 16, to be exact – Jobs announced that he was now Apple's "interim CEO".

As interim top dog, Jobs quickly instituted what he referred to as his "Loose lips sink ships" policy, named after those ubiquitous World War II posters that warned Americans to keep their mouths shut in case an enemy might be listening. Apple had previously allowed journalists access to engineers, and had preannounced its products to us ink-stained wretches under nondisclosure agreements. But upon Jobs' arrival the company clammed up – a policy that continues to this day.

In addition to killing the clone dragon and pulled up the drawbridge, Jobs looked inside the Cupertinian castle and saw a disorganized morass of often-duplicative and hardly category-leading products.

As Jobs explained it to the assembled developers at 1998's Worldwide Developers Conference, "What I found when I got here was a zillion and one products" – well, to be more accurate, there were 15 different Mac platforms, plus servers, monitors, scanners, and printers.

"And I started to ask people," he continued, "why would I recommend a 3400 over a 4400? Or when should somebody jump up to a 6500, but not a 7300? And after three weeks, I couldn't figure this out.

And I figured if I can't figure it out working inside Apple with all these experts telling me in three weeks, how are customers ever going to figure this out?"

Jobs' solution was to drastically cut the number of platforms that Apple produced from 15 to four, which he described in a product matrix of consumer and pro platforms on the x axis and portable and desktop platforms on the y axis.

That matrix had no place for either the hardware or software aspects of the Newton program. On February 27, 1998, Apple announced that it was ending all Newton development, which meant the end of Apple's two Newton-platform products of the time, the stylus-operated MessagePad 2100 and the keyboard-equipped eMate 300.

The Newton had been John Sculley's baby, and when asked if Jobs killed the Newton out of revenge for being maneuvered out of Apple in 1985, Sculley replied: "Probably. He won't talk to me, so I don't know."

The two "pro" boxes in Jobs' matrix were already filled by the Power Mac G3 and PowerBook G3 were introduced in November 1997. They, however, were outgrowths of Apple's older design language: the original Power Mac G3 was a traditional beige box, and the PowerBook G3 was essentially a refinement of previous PowerBooks.

It was the consumer desktop that Jobs introduced on May 6, 1998, that was the turning point in Apple's design thinking. Many have also argued that it was also the end of Apple's death spiral and the beginning of Jobs' meteoric ascent.

That consumer desktop was the iMac. While Jobs is widely credited for its creation, its basic design had been kicking around Apple for some time, designed by the man who since 1996 has been Apple's lead designer: Jonathon Ive.

Ive had been hired at Apple in 1992, but his design sense – he was a devotee of Braun designer Dieter Rams – hadn't been appreciated in Apple's corner offices. As a former colleague of Ive's told The Observer, "There is a rumour Apple had designed the iMac years earlier but the existing boss was not interested, so they put it away. When Jobs returned and asked what ideas they had, Jonathan brought it out and the rest is history."

Jobs is also often credited with having the foresight to add USB and drop the floppy drive from the iMac, but credit for those decisions should at least be shared by Jon Rubinstein, Apple's hardware-engineering lead who had left NeXT a few years before that company's acquisition by Apple, and whom Jobs introduced to Amelio and suggested he hire.

It was Rubenstein who managed the breakneck pace of the iMac's development that enabled it to make it to its May 1988 coming-out party. That event, not coincidentally, was held in the same Flint Center auditorium in Cupertino where the original Mac made its debut in 1984. Also not coincidentally, when Jobs introduced the iMac it gave the audience the same greeting, in the same script font, that the orginal Mac had 14 years earlier: "Hello" – but with the addition of "(again)".

One other person deserves mention: Ken Segall of Apple's ad firm TBWA\Chiat\Day, who gave the iMac its name. Segall told The Cult of Mac in 2009 that Jobs had suggested another name that Segall considered so bad it would "curdle your blood" – though he wouldn't divulge Jobs' suggestion. Jobs originally hated the name "iMac", Segall says, but eventually warmed to it.

Jobs certainly presented the iMac at its introduction with warmth and affection. After enumerating the shortcomings of contemporary consumer computer, he dismissed their desgn by saying "these things are uggggly. The iMac, on the other hand, was a whole new design ball game. "The whole thing is translucent – you can see into it," Jobs enthused. "It's so cool!"

Jobs also touted the iMac's "coolest mouse on the planet" – an evaluation that many disagreed with – and the iMac's 360-degree design. "The back of this thing looks better than the front of the other guys'," Jobs said. "It looks like it's from another planet – and a good planet. A planet with better designers."

Inside its translucent Bondi-blue-and-white shell, the original iMac had decent specs for a consumer-level computer of its time: a 233MHz G3 processor with 0.5MB backside cache, 32MB RAM expandable to 128MB, 100Mbps Ethernet, 33Kbps modem, 4Mbps iRDA, 4GB hard drive, and a tray-loading 24x CD-ROM drive.

But what sold the iMac wasn't its specs, it was its looks and its plug-and-play simplicity. It can be argued that the iMac represented an inflection point in consumer-computer sales: prospective buyer no longer asked their computer-savvy friends to interpret megahertz and gigabytes for them, they simply saw what they liked and bought it.

On the consumer side, Jobs went on to follow that "Keep it simple, stupid" philosophy with the iPod, the iPhone, and the iPad, and rode it all the way to the bank. On the day that the iMac was first introduced – three months before it shipped on August 15 – Apple's stock was selling for $7.58 per share. Hmmm... Let's check what it's going for today.

It seems that Jobs was onto something.

10 Most Memorable Steve Jobs CEO Moments

Internet Mourns Steve Jobs' Death

Samantha Murphy, TechNewsDaily Senior Staff Writer

Apple announced in a statement posted to its company site that its founder and former CEO died after his long battle with pancreatic cancer. In 2004, Jobs received a liver transplant and took several medical leaves of absences in recent years before finally resigning as CEO of Apple this summer.

“You inspired millions and changed the way we look at technology,” Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg wrote on his Facebook page. “No yardstick of quality could measure your actions.”

At press time, nearly 65,000 people “liked” Zuckerberg’s status, with many adding their own condolences to the message.

Facebook members also flocked to Job’s profile page to share their condolences. Many also took to the wall of Steve Wozniak, Job’s long-time business partner and Apple co-founder. [Read: Steve Jobs and Apple Through The Years (Infographic)]

“My condolences, Steve, on the passing of your business partner and friend,” wrote Bruce Ansley from Baltimore, Maryland. “Together you helped usher in a new era and countless lives have been enhanced because of your efforts and that of Steve Jobs, may he rest in peace.”

Microsoft Chairman Bill Gates wrote a message on Facebook to address the news:

“Steve and I first met nearly 30 years ago, and have been colleagues, competitors and friends over the course of more than half our lives. The world rarely sees someone who has had the profound impact Steve has had, the effects of which will be felt for many generations to come,” Gates wrote."I will miss Steve immensely."

President Barack Obama also released a statement on WhiteHouse.gov: “Michelle and I are saddened to learn of the passing of Steve Jobs. Steve was among the greatest of American innovators - brave enough to think differently, bold enough to believe he could change the world, and talented enough to do it,” Obama said.

“By building one of the planet’s most successful companies from his garage, he exemplified the spirit of American ingenuity,” Obama said. “By making computers personal and putting the internet in our pockets, he made the information revolution not only accessible, but intuitive and fun.”

Meanwhile, phrases such as “ThankYouSteve,” “RIP Steve Jobs” and “iSad” immediately began to trend on Twitter following the news. “Pixar” also shot up to the top of the trending list, as many remembered Jobs’s role as former Pixar chief and Disney executive.

Those in the tech industry weren’t the only ones to share words of sympathy on social networking sites: “Steve lived the California Dream every day of his life and he changed the world and inspired all of us,” Arnold Swarzenegger wrote on Twitter.

News of Jobs’ death comes one day after the company unveiled the fifth generation of the iPhone, the iPhone 4S, which Jobs played in integral role in developing.

“I have always said that if there ever came a day when I could no longer meet my duties and expectations as Apple’s CEO, I would be the first to let you know,” Jobs wrote in a letter released by the company when he left. “Unfortunately, that day has come.”

This story was provided by TechNewsDaily , sister site to LiveScience. Reach TechNewsDaily senior writer Samantha Murphy at smurphy@techmedianetwork.com.Follow her on Twitter @SamMurphy_TMN

Newscribe : get free news in real time

Steve Jobs: from parents' garage to world power

Highlights from the life of pioneering inventor and Apple co-founder who has died aged 56

- David Batty

1955 Steve Jobs is born in San Francisco on 24 February 1955, and adopted by Paul and Clara Jobs of Mountain View, California.

1974 He takes a job at videogame company Atari Inc but resigns after a few months to travel to India.

1975 Jobs and his friend Steve Wozniak build a prototype computer in the garage of Jobs' parents.

1976 Jobs and Wozniak co-found Apple Computer to sell their machines, staring with the Apple I.

1977 The Apple II is launched. The first successful mass-market computer, it remains in production for 16 years.

1980 The company's second computer, the Apple III, is launched but proves a commercial failure, plagued by faulty construction.

1983 Apple launches the Lisa, the first personal computer controlled by on-screen icons activated at the click of a mouse. But it also proves unsuccessful.

1984 Apple launches the Macintosh computer, which wins rave reviews but suffers disappointing sales.

1985 Apple closes half its six factories, sheds 1,200 employees (a fifth of its staff) and declares its first quarterly loss. Jobs loses a boardroom battle against John Sculley and is forced out of the company.

1986 Jobs buys the computer graphics division of Lucasfilm Ltd, the company owned by Star Wars director George Lucas, and founds what would become Pixar Animation Studios.

1987 Macintosh II is launched in 1987. 1988 Jobs founds NeXT Computer, but it was not a financial success, selling only 50,000 computers.

1995 With Jobs as its chief executive, Pixar releases Toy Story, the first full-length computer animated film, which is a worldwide box office smash.

1996 Apple buys NeXT for $429m (£277m) and uses Jobs' technology to build the next generation of its own software.

1997 Jobs becomes Apple's interim chief executive.

1998 The iMac is launched, a self-contained computer and monitor. Its design eclipses the clunky build of Apple's competitors.

2001 The first iPod goes on sale in October and proves a huge success.

2003 The iTunes music store is launched in April.

2007 The first iPhone is launched. Jobs decides to drop the computer part of Apple's name.

2010 The iPad is launched in April and 3m of the devices are sold in 80 days. Nearly 15m iPads are sold worldwide by the end of the year. Apple's annual sales reach $65bn – a huge rise from $8bn in 2000.

2011 Apple continues to roll out new products to great demand including the iPad 2 and iPhone 4.

1974 He takes a job at videogame company Atari Inc but resigns after a few months to travel to India.

1975 Jobs and his friend Steve Wozniak build a prototype computer in the garage of Jobs' parents.

1976 Jobs and Wozniak co-found Apple Computer to sell their machines, staring with the Apple I.

1977 The Apple II is launched. The first successful mass-market computer, it remains in production for 16 years.

1980 The company's second computer, the Apple III, is launched but proves a commercial failure, plagued by faulty construction.

1983 Apple launches the Lisa, the first personal computer controlled by on-screen icons activated at the click of a mouse. But it also proves unsuccessful.

1984 Apple launches the Macintosh computer, which wins rave reviews but suffers disappointing sales.

1985 Apple closes half its six factories, sheds 1,200 employees (a fifth of its staff) and declares its first quarterly loss. Jobs loses a boardroom battle against John Sculley and is forced out of the company.

1986 Jobs buys the computer graphics division of Lucasfilm Ltd, the company owned by Star Wars director George Lucas, and founds what would become Pixar Animation Studios.

1987 Macintosh II is launched in 1987. 1988 Jobs founds NeXT Computer, but it was not a financial success, selling only 50,000 computers.

1995 With Jobs as its chief executive, Pixar releases Toy Story, the first full-length computer animated film, which is a worldwide box office smash.

1996 Apple buys NeXT for $429m (£277m) and uses Jobs' technology to build the next generation of its own software.

1997 Jobs becomes Apple's interim chief executive.

1998 The iMac is launched, a self-contained computer and monitor. Its design eclipses the clunky build of Apple's competitors.

2001 The first iPod goes on sale in October and proves a huge success.

2003 The iTunes music store is launched in April.

2007 The first iPhone is launched. Jobs decides to drop the computer part of Apple's name.

2010 The iPad is launched in April and 3m of the devices are sold in 80 days. Nearly 15m iPads are sold worldwide by the end of the year. Apple's annual sales reach $65bn – a huge rise from $8bn in 2000.

2011 Apple continues to roll out new products to great demand including the iPad 2 and iPhone 4.

Newscribe : get free news in real time

The life and times of Steven Paul Jobs, Part One

By Rik Myslewski in San Francisco • Get more from this authorWhen sober, F. Scott Fitzgerald may have been devastatingly intelligent, but he got it dead wrong when he wrote "there are no second acts in American lives."

Think Elvis, for example. Or lefty sinkerballer Tommy John of the eponymous surgery. Or, for that matter, Grover Cleveland, whose two acts as US president were separated by a four-year intermission.

In the business world, however, second acts are rare. In the corporate rat race, if you slip in Act I, you're trampled by your fellow rodents – there's no "Tomorrow, and tomorrow, and tomorrow" on that unforgiving stage.

Except for Steve Jobs.

The career of Apple's cofounder and savior not only had a second act, but a long and successful third act that ranged from his return to Apple in 1997 to his resignation this August.

And to further give the lie to Mr. Fitzgerald, Jobs' second act held true to the dramaturgical dictum that as the curtain closes on Act II, our protagonist should be at the end of his rope, facing seemingly insurmountable odds.

Think The Empire Strikes Back, Act II of the original Star Wars trilogy. Think the Red Sox being down three games to zip against the Yankees in 2004. Think Steve Jobs at the end of 1993, with NeXT's hardware business sold at fire-sale prices and Disney stopping the development of Pixar's salvation, Toy Story.

Steve Jobs in April 2010

The end of Jobs' redemptive and triumphant Act III, his death on Wednesday, could be thought to have turned his drama into a tragedy – but possibly more from our points of view than from his. By all accounts, he retained throughout his life the sense of light mortality that he gained when studying eastern philosophies in his youth.

"We're born, we live for a brief instant, and we die." he told Wired in 1996. "It's been happening for a long time."

Speaking at Stanford University in 2005, he said, "No one wants to die. Even people who want to go to heaven don't want to die to get there. And yet death is the destination we all share. No one has ever escaped it. And that is as it should be, because Death is very likely the single best invention of Life. It is Life's change agent."

And in 2008 he told Fortune, "We don't get a chance to do that many things, and every one should be really excellent. Because this is our life.

"Life is brief, and then you die, you know? So this is what we've chosen to do with our life."

And so here's a recounting of the life that Steve Jobs chose – and the life that chose him.

The early years

Jobs was born in San Francisco on February 24, 1955. Shortly thereafter he was adopted by Paul and Clara Jobs of the same city, who had married in 1946 but had been unable to have a child of their own. They named their new son Steven Paul Jobs.Jobs' biological parents were Joanne Schieble of Green Bay, Wisconson, and Syrian-born Abdulfattah Jandali, unmarried, both 23, and both students at the University of Wisconsin in Madison. It being the straight-laced mid-1950s, for the birth they secretly travelled to San Francisco, a few miles north of a sleepy, orchard-filled patch of Northern California that Jobs would one day help transform into Silicon Valley.

Adoptive father Paul, described by son Steve as "a sort of genius with his hands" in a 1985 Playboy interview, "used to get me things I could take apart and put back together."

Just as, in his later years, he took apart and put back together the company he founded, Apple Computer, when he returned to it in 1997 after a palace coup in 1985 had forced him out of the company that he had founded on April Fools' Day 1976 with Steve Wozniak and Ronald Wayne.

But we're getting ahead of ourselves.

Steve Jobs as a boy

The Jobs family moved to 2066 Crist Drive in Los Altos in the heart of pre-silicon Silicon Valley when Steve was five years old. As a kid, Jobs admitted, he was "a little terror." Today he might have been diagnosed as showing symptoms of ADHD – attention deficit hyperactivity disorder – and have been Adderalled or Ritalinned into submission.

"You should have seen us in third grade," Jobs described himself and his pint-sized co-revolutionaries. "We basically destroyed our teacher. We would let snakes loose in the classroom and explode bombs."

The 1950s may not have been enlightened enough to have accepted Schieble and Jandali's out-of-wedlock child, but neither was it a time when exploding bombs in a public school would call down the wrath of the Department of Homeland Security. In those days, Jobs' behavior was merely part of the "boys will be boys" ethos.

A fourth-grade teacher, Imogene Hill, who Jobs described as "one of the saints in my life," helped tame his rambunctiousness – partially by bribing him with cash if he'd finish his work, according to Anthony Imbimbo's biography written for young adults, Steve Jobs: The Brilliant Mind Behind Apple.

Steve Jobs, front and center. Already

When in junior high, Jobs hung out with his friend and fellow geek Bill Fernandez, who – fortunately for the future of personal computing – lived across the street from the Wozniak family, whose son Steven was an inveterate electronics tinkerer.

Steve Wozniak was born in August 1950, making him five years older than Jobs. Despite their age difference, they bonded over their shared love of both electronics and pranks.

In 2007, when giving a Macworld Expo presentation, Jobs' slide-changing clicker malfunctioned. To fill time, he told his audience about one prank that he and Wozniak played when the older prankster was a student at the University of California at Berkeley:

When he was in his mid-teens, Jobs and Wozniak met the famous – infamous? – phone phreaker John Draper (aka Cap'n Crunch, so named after he discovered that a whistle given away in the eponymous cereal could phool fool AT&T's phone system). Inspired by the good Cap'n's success, Wozniak built what was then called a "blue box" – an electronic device that enabled him and friend Jobs to make free phone calls worldwide.

"The famous story about the boxes is when Woz called the Vatican and told them he was Henry Kissinger," Jobs told Playboy. "They had someone going to wake the Pope up in the middle of the night before they figured out it wasn't really Kissinger."

The blue box was Wozniak and Jobs' first commercial product, and established the relationship that would eventually result in the creation of Apple Computer: Wozniak would design, and Jobs would sell.

After high school – and after he had abandoned the blue-box business – Jobs headed off to Reed College in Portland, Oregon, then a notorious hippie haven, well-suited to increasingly hippified Jobs.

He lasted one semester, but continued to live on-campus – not a problem at Reed, nor for that matter at any number of schools during the laid-back early 1970s.

His position at Atari got him a tech-troubleshooting trip to Germany, which he extended into a classic hippie pilgrimage to India, where he wandered as an alms-begging mendicant, and famously had his head shaved by a highly amused Indian holy man.

After returning to California – shaved head and all – Jobs was rehired by Atari, and hooked back up with Wozniak. At that point, Wozniak was working at HP, but he would visit Jobs at night at Atari to play that company's Gran Track game for free.

"Woz was a Gran Track addict," Jobs told Playboy. "He would put great quantities of quarters into these games to play them, so I would just let him in at night and let him onto the production floor and he would play Gran Track all night long." But Jobs wasn't being merely magnanimous: "When I came up against a stumbling block on a project, I would get Woz to take a break from his road rally for ten minutes and come and help me."

Jobs also used Wozniak's smarts to design that company's Breakout game. According to Jeffrey Young and William Simon is their unauthorized biography, iCon Steve Jobs, along with other sources, Jobs took credit for the design and snookered Wozniak out of his rightful share of the pay and bonus that Jobs was given for "his" work.

The "Good Steve" versus "Bad Steve" dynamic that would mark Jobs' persona for the rest of his life was already in place.

The birth of Apple Computer

Nineteen seventy-five is generally agreed to be the year that the personal computer was born, when the Altair 8800 kit was announced on the cover of Popular Electronics' January issue.Shortly after that epoch-making event, a group of electronics enthusiasts formed the Homebrew Computer Club. In addition to Jobs and Wozniak, members included such soon-to-be-luminaries as George Morrow, Adam Osborne, and Lee Felsenstein. It was among that heady company that Wozniak developed the first prototypes of what was to become the Apple I.

Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak in 1975

Where Wozniak saw a diverting intellectual challenge, Jobs saw a business opportunity. After the debut of the Altair, "microcomputer" kits were appearing right and left, and Jobs believed that Wozniak's designs – one for a color-capable computer, no less – could find a market.

After some cajoling, Wozniak agreed to Jobs' suggestion that they form a company, and that the company should be named Apple Computer. Although the true source of the name remains cloudy – was it that apples were grown on a commune that Jobs had recently visited, the fact that "Apple" would appear ahead of "Atari" in the phone book (remember phone books?), a tribute to The Beatles? – it was Jobs' idea and Wozniak agreed to it.

On April 1, 1976, Jobs, Wozniak, and Ronald Wayne – a friend of Jobs from Atari who dropped out of the new company less than two weeks later (and who recently published an autobiography) – signed the paperwork that created Apple Computer. With an order for 50 fully assembled Apple I computers from a tiny Mountain View, California, geek emporium called the Byte Shop, and with the proceeds of the sale of Wozniak's HP-65 calculator and Jobs' VW van, the company was up and running.

The Apple I was less than a rip-roaring success, selling around 200 units, total. Jobs reportedly wanted to sell it for $777.77, but Wozniak thought that was too expensive, so the price was dropped to $666.66 – around $2,500 in today's dollars.

Wozniak's next creation, the Apple II, was a different animal entirely. Wozniak said it should have expansion slots, so it had expansion slots. Jobs said i shoul run without a fan, so they hired someone to invent the smaller, cooler, switching power supply.

By far more important, however, was a decision by Jobs and Wozniak that would affect all of Apple's future product development: the Apple II would be a complete system designed for ease of use, simple operation, and consumer friendliness. Industrial design was also on Jobs' mind: no screws disturbed the Apple II's plastic exterior – they all were on the bottom of its all-plastic case.

A fully tricked-out Apple II – every geek's object of lust (source: oldcomputers.net

Jobs made one more key move at this time: he landed a key investor and business adviser, Mike Markkula, who got the two founders to incorporate Apple in January 1977. Markkula also introduced the duo to Mike Scott, and convinced them to hire him as president of the fledgling outfit. Scott and Jobs clashed almost immediately, the first of many such battles that would lead to Jobs' eventual ouster.

On April 17, 1977, the Apple II debuted at the West Coast Computer Faire, and – as each and every Apple press releases noted for many years afterwards – "ignited the personal computer revolution."

The Macintosh

In 1979, Jobs made his now-famous visit to Xerox PARC (Palo Alto Research Center), a drop-in that – at the risk of hyperbole – changed him, Apple, and personal computing forever:"They showed me really three things," he said in an interview in the PBS series "Triumph of the Nerds" in 1996. "But I was so blinded by the first one I didn't even really see the other two" – those two being the object-oriented programming language SmallTalk, created by Alan Kay and others, and a fully network collection of over 100 Xerox Alto computers hooked up over Bob Metcalfe's Ethernet.

"I was so blinded by the first thing they showed me which was the graphical user interface," Jobs recalled. "I thought it was the best thing I'd ever seen in my life." He left Xerox PARC determined that Apple would bring GUI-based computing to the masses.

Apple's Lisa – this one with the notorious "Twiggy" drive upgraded to a Sony 400KB "microfloppy" (click to enlarge)